Research Article

Comorbidity of alcohol dependence with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and the role of executive dysfunctions

Gloria Tosi1, Giovanni Vittadini1, Ines Giorgi1, Caterina Pistarini2*, Elena Fiabane2,3 and Paola Palladino3

1Psychology Unit, ICS Maugeri Spa SB, Scientific Institute of Pavia, Italy2Department of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, ICS Maugeri Spa SB, Institute of Genoa Nervi, Italy

3Department of Brain and Behavioral Sciences, University of Pavia, Italy

*Address for Correspondence: Caterina Pistarini, Department of Physical & Rehabilitation Medicine, ICS Maugeri Spa SB, Institute of Genoa Nervi, Via Missolungi 14, Nervi, Genoa 16167, Italy, Tel: +39 010 30791250; Fax: +39 010 3079 1269; Email: [email protected]

Dates: Submitted: 16 January 2018; Approved: 29 January 2018; Published: 30 January 2018

How to cite this article: Tosi G, Vittadini G, Giorgi I, Pistarini C, Fiabane E, et al. Comorbidity of alcohol dependence with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and the role of executive dysfunctions. J Neurosci Neurol Disord. 2018; 2: 001-010. DOI: 10.29328/journal.jnnd.1001008

Copyright License: © 2018 Tosi G, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Alcohol dependence; ADHD; Executive function

Abstract

Background: This study aims to retrospectively investigate the comorbidity of ADHD multiple symptoms (behavioral) with alcohol addiction in a sample of adult alcohol-dependent patients and to test their current attentional skills (behavioral and cognitive).

Methods: Thirty-two adult alcohol-dependent patients were examined for ADHD using a semi-structured interview and the Mini Mental State Examination to evaluate attention and inhibition functions. Brown ADD Scales were used to specifically examine ADHD syndrome. Patients were compared with thirty matched control participants selected from healthy population in few measures of attentional control and working memory.

Results: 50% of patients showed evidence of primary ADHD symptoms: specifically, 28.12% showed criteria for ADHD highly probable, 12.50% for ADHD probable but not certain and 9.38% for ADHD possible but not likely. Patients also revealed several deficits in the selective visual attention, interference control and verbal working memory compared to the control group.

Conclusions: These results revealed that adult alcohol-dependent patients had retrospectively high comorbidity with ADHD and significant current deficits of the executive functions. These findings suggest the importance of early diagnosis and treatment of ADHD in order to prevent the development of alcohol dependence.

Introduction

The Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is defined as a disorder of the neuropsychological development characterized by the following nuclear symptoms: attention deficit, increased impulsiveness, hyperactivity, disorganization and emotional instability [1]. ADHD in adulthood is considered a hidden disorder where common diagnostic criteria are lacking, therefore adult patients who often arrive for consultation are more frequently diagnosed with ADHD in comorbidity than with ADHD itself [2,3]. This makes it difficult to detect the disorder and, in most cases, it has been noticed that it was associated with other psychiatric conditions, such as Bipolar Disorder, Depressive Syndrome, Antisocial and Narcisistic Personality Disorder, Borderline Personality Disorder, General Anxiety Disorder and Panic Disorder [4,5]. However, previous studies have identified significant variability in ADHD prevalence estimates worldwide [4]. In addition, in spite of it being historically considered a distinctive childhood disorder, till today it has been certified that ADHD persists in adulthood in 50-80% of the individuals that satisfy the criteria for the disorder during childhood [4,6]. For example, a prevailing disorder between 2-6% has been estimated in adult population, whereas in a research study carried out in 2006 by Kessler et al., a widespread 4.4% has been certified amongst adults in the United States [7].

It is worth to notice that children with ADHD are significantly more likely to develop substance use disorders than children without ADHD [8-10]. Indeed, previous studies have already shown that ADHD is a risk factor for the onset and the development of addiction to substances, like alcohol and drugs [11-13]. For example, the study of Jacob et al. (2007), showed a level of comorbidity of ADHD and abuse of substances in approximately 71% of the participants. It was discovered that there is 45% of prevalence in the entire life of adults with ADHD for the disorder of substances abuse: the participants with the disorder and addiction to substances had a more precocious start and a tendency to experiment them more freely than addicted participants without ADHD [13]. On their side, Wilens et al. [12], confirmed the comorbidity between ADHD and alcoholism or substance abuse in 35-70% of the cases.

A high incidence of alcohol abuse in patients with ADHD was found in other studies. On the other hand, Ramussen and Gilberg (2000), have noticed an increased incidence of alcohol abuse in a controlled longitudinal study on 55 patients aged 22 years old with ADHD diagnosed in their childhood and not treated with a pharmacological therapy. Krause et al. (2002), carried out a research on 153 adult patients dependent on alcohol and they found an evident ADHD in 65 of them during their childhood, 28 of whom maintained these symptoms in adulthood.

Previous studies showed that a dysfunction of the executive functions (EF), settled in the prefrontal region, has been detected both in children as well as in adults with ADHD [14-16]. The executive functions include a series of cognitive abilities of a higher level that enable us to use appropriate behaviours in the context and to achieve a goal. The main cognitive processes include: planning, mental flexibility, decision making, inhibition of irrelevant stimuli, controlling the interference and working memory (see for example, Barkley 1998). These cognitive processes have been mainly studied in patients with ADHD during their childhood, while very few studies have been carried out in adults with the disorder and contrasting results were found. For example, previous studies [14,17] demonstrated that adult participants with ADHD have a poorer performance in the verbal working memory and attentive abilities (such as interference control, selective and divided visual attention), if compared to healthy control population. At the same time, other studies [16,18] have shown no significant differences between adults with ADHD and a control group.

Scientific research on comorbidity of ADHD with alcohol abuse from both a clinical and cognitive prospective is therefore seriously limited [13] and needs to be further explored. The aim of the present study was to retrospectively investigate the comorbidity of ADHD nuclear symptoms (behavior) in alcohol-dependent adults and to examine their current cognitive performance in executive functions (i.e., visual selective attention, shifting abilities and inhibition).

Methods

Participants

A total of 32 adult patients with a diagnosis of Alcohol Dependence according to the the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Revised – DSM-IV-TR Fourth Edition (APA, 2000) gave their consent to participate in this study. They were consecutively recruited at the Alcohol Rehabilitation Unit in a Rehabilitation Institution in Northern Italy. The examination was performed after a 10-day detoxification therapy in order to ensure that patients had any withdrawal symptoms. The exclusion criteria were: acute psychosis and other pathologies which may influence the subject’s ability to undergo the exams; cognitive impairment (defined as a score lower than the cut off (=23) for the Mini Mental State Examination); the presence of other serious problems associated to attention disorders, as for instance permanent auditory and visual deficits. In this study, the sample of patients with a diagnosis of Alcohol Dependence (n=32) were compared to a control group, composed of 30 healthy participants selected at random from the general population but matched to the clinical sample for gender, age, education, marital status and employment status.

Procedure and measures

The version for adult participants Brown ADD Scales [19] was used to explore a retrospective history of ADHD and the possible persistence of the symptoms in adulthood. The instrument comprised a Self-scoring Module and a Diagnostic schedule, including seven sections designed to conduct a comprehensive diagnostic assessment of ADHD. The evaluation procedure lasted about an hour. The Self-scoring Module was composed of 40 items which referred to DSM-IV criteria, allowed to highlight if the sum of the scores associated with the symptoms falled within the range necessary to formulate a diagnosis of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. The cumulative rates (T points for the Italian version) [19] indicated the severity of the deficit for each of the five clusters in which the symptoms were grouped together, since they allowed us to compare the values obtained from the subject with those of a regulatory non-clinical population of the same age. T points represented a practical way to determine the specific groups of symptoms related to the syndrome that were particularly problematic for an individual. A T points total score of 55 was equal to the cut off reference. T points equal to or greater than 65 usually indicated the presence of relevant problems. A total T-score greater than or equal to 55 indicated that the subject had a significant probability of fulfill the diagnostic criteria of ADHD. If the participant got a T-score less than 55, it was possible but unlikely that they met the diagnostic criteria di ADHD. If the participant got a score that approximated or was greater than the threshold level clinical, a more detailed assessment was required, because there was the possibility of a sospicious ADHD-ADD. Participants who scored below the threshold level and not showing obvious signs of ADHD-ADD may not be needed further study aimed to investigate the diagnosis.

Additionally, in this study the Self-scoring Module was also used to divide patients into sub-groups with ADHD (inattentive type, impulsive type, combined type) and without ADHD. Since the problems of executive functions underlying the syndrome were complicated and involved several sub-functions, a proper assessment had required an integration of different types of information. Visual Selective attention and shifting ability were assessed using the Trail Making Test (Retain, 1958) and Attentive Matrixes (Spinnler & Tognoni, 1987). Selective attention and interference control were assessed by using an adaptation of a Working Memory Task [20,21]. It was composed of a Working Memory Span Test with Categorization (WMC), which consisted of a dual task of Primary Recall Task and Detection Task of targets (animal nouns), and a Lexical Decision inhibition-priming Task.

Working Memory Span Test with Categorization: Sets of three series containing a growing number of strings of words (from two to four) were presented to the participants via a computer screen (SUPERLAB software). Each string contained four high- to medium-frequency words. Strings contained 0, 1 or 2 animal nouns, which could have been presented in various locations, including the final positions. The participant had to tap when she or he heard an animal noun (“bee”, for example) and had to remember the last words in each string at different levels of difficulty (the level of difficulty consists of the numbers of words to be remembered for each list, from 2 to 5 words). For example, at level 3 the words the participant had to remember are 3, and so on to the level of difficulty 5.

The animal noun Detection Task would induce a difference in activation between animal nouns (more activated) and nonanimal nouns (less activated). The participant’s task was to read each word out loud and to press the space bar when an animal noun was presented. After each series the request “RICORDA” (REMEMBER) appeared on the screen, and the participant had to recall the last word of each string in serial order. For about half of the series, in a fixed random order, the Recall Task was immediately followed by a lexical decision task.

Lexical Decision Task: This task consisted of a computer presentation of the same number of words and nonwords, immediately after a final recall of the last word of each set, for each level of difficulty. Of these items, half were a representative sample of the words included in the just-presented series as nonfinal words (2 were non animal nouns, and 2 were animal nouns), and the other half were words that were not part of the material of the working memory span but had similar characteristics. The equal proportion of animal versus nonanimal nouns was presented in order to examine the potential difference due to the activation gained during the memory task. The participant’s task was to decide as soon as possible whether the presented item was a word, pressing YES if the item was a word (for example “figlio”) and NO if it was a nonword (for example “copsi”). Accuracy and time were recorded.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to present the characteristics of participants. In order to compare the groups of patients (with ADHD and without ADHD) and the control group, Pearson’s χ2 test for categorical variables and Repeated Measure Analysis of Variance (RM ANOVA) for continuous variables were used. Post-hoc comparisons were carried out using the estimates marginal means method or t test (Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons). Data were analyzed using SPSS 13.0 (Statistical Package for Social Science, Windows version, Chicago, Illinois).

Results

The sample of patients with a diagnosis of Alcohol Dependence (AD) included a majority of males (68.8%) with an average age of 45.53 (±9.10) years. Most of patients were unmarried (53.1%), employed (53.1%) and with an average education of 11.41 (±3.14) years. The control group was matched for gender with the clinical group in order to have a majority of males (60.0%) with an average age of 38.60 (±11.20) years not far from that of the AD group. The majority of the control group was engaged (53.3%), employed (63.3%) with an average education of 13.47 (±2.19) years.

The socio-demographic characteristics of the three samples are represented in table 1 and showed that the control group has a significant lower age (p=0.01) and higher education (p<0.05) than alcohol-dependent patients. Specifically, post hoc tests revealed that age significantly differ between control group and alcohol dependence patients without ADHD (p<0.05) and that education significantly differ between control group and alcohol dependence patients with ADHD (p<0.05).

| Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of the three groups of samples. | ||||

| Variablesa | Alcohol dependence with ADHD (DSM-IV) (n=16) | Alcohol dependence without ADHD (DSM-IV) (n=16) |

Control Group (n=30) | P-value |

| Gender | ||||

| Males | 13 (81.3) | 9 (56.3) | 18 60.0) | 0.26 |

| Females | 3 (18.8) | 7 (43.8) | 12 (40.0) | |

| Age (years), Mean±SD | 44.13 (±7.58) | 46.94 (±10.47) | 38.60 (±11.20) | 0.03 |

| Education, Mean±SD | 11.06 2.95 | 11.75 3.37 | 13.47 (±2.19) | 0.01 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married, n (%) | 4 (25.0) | 4 (25.0) | 16 (53.3) | 0.15 |

| Unmarried, n (%) | 9 (56.3) | 8 (50.0) | 12 (40.0) | |

| Widower/Divorced, n (%) | 3 (18.8) | 4 (25.0) | 2 (6.7) | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed, n (%) | 10 (62.5) | 7 (43.8) | 19 (63.3) | 0.40 |

| Unemployed | 6 (37.5) | 8 (50.0) | 8 (26.7) | |

| Retired | 0 (0) | 1 (6.3) | 3 (10.0) | |

| aCategoric data are shown as number (%) and continuous data as mean (SD). | ||||

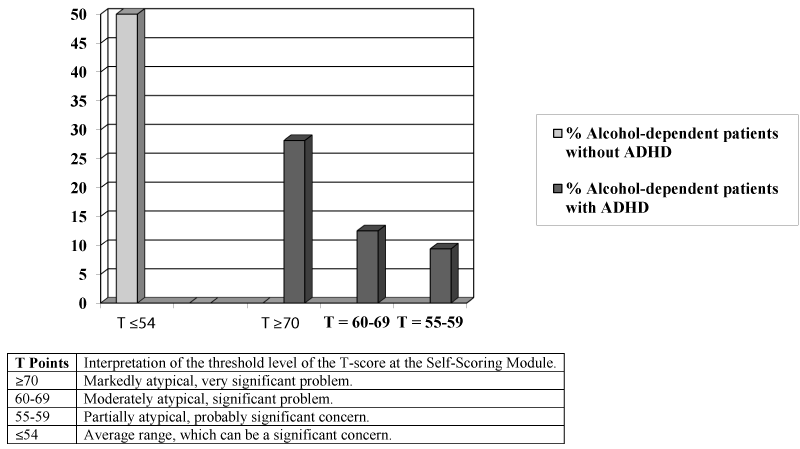

On the basis of the results of the Self-Scoring Module of the Brown ADD Scales, alcohol-dependent patients were divided in two groups: 1) participants with a diagnosis of alcohol dependence without ADHD and 2) participants with a diagnosis of alcohol dependence with ADHD. Results of Brown ADD Scales are shown in figure 1. It reveals that 16 (50%) alcohol-dependent patients fulfilled the criteria for ADHD symptoms, according to DSM-IV, in the Self-Scoring Module (T points totals ≥55=highly likely ADHD). Among these 16 patients, 9 (28.13%) obtained T points totals ≥70, indicating a presence of an evidently atypical symptomatology which is to be considered very meaningful of a possible ADHD diagnosis; 4 participants (12.50%) obtained T points totals between 60-69, indicating a moderately atypical problem which is to be considered meaningful; 3 participants (9.38%) obtained T points totals between 55-59, indicating a partially atypical symptomatology which is likely to be meaningful.

Figure 1: Summary of diagnostic conversion of T points total scores obtained at the Self-scoring Module (pathological sample n=32).

| T Points | Interpretation of the threshold level of the T-score at the Self-Scoring Module. |

| ≥70 | Markedly atypical, very significant problem. |

| 60-69 | Moderately atypical, significant problem. |

| 55-59 | Partially atypical, probably significant concern. |

| ≤54 | Average range, which can be a significant concern. |

Additionally, a diagnostic division of the ADHD subtypes was carried out according to the criteria of DSM-IV. It emerged that 6 patients (18.75%) were diagnosed as Predominant Inattention Type, 3 patients (9.38%) as Predominant Impulsive-Hyperactivity Type, 1 patient as Combined ADHD Type. Finally, 6 participants are in the Non-specified ADHD Type for those inattention or impulsive-hyperactivity disorders which do not fully satisfy the foreseen diagnostic criteria. Results obtained from the assessment of the global cognitive functioning (Trail Making Test and Attentive Matrixes) are shown in table 2. No significant differences amongst the three groups were found in the Trail Making Test (F (2.59)=2.89; p>0.05; η²=0.089), while a significant difference was found in the Attentive Matrixes test (F (2.59)=4.98; p=0.01; η²=0.144). Post hoc comparisons (Bonferroni correction: p<0.01) revealed that the group with ADHD reported worse performance in the selective attention and in the visual-spatial research (Attentive Matrixes) than the control group (mean difference=0.62; p=0.02). The two groups of patients with and without ADHD were compared to the control group in the examination of executive functions. Before illustrating the results of the participants examined at the working memory task [20,21], it must specify that the group of participants without ADHD and the group of participants with ADHD did not perform the primary recall task. In fact it has emerged, since the beginning of the test, a deficit in retaining in mind the target words that had to be stored and reported during the task for each level of difficulty. For this reason, it was analyzed the performance of the participants with exclusively regards to the Detection Task in which they had to press the space bar each time at the flow of the words on the monitor they recognized a target stimulus (animal noun).

| Table 3: Means (and Standard Errors) of correct detections for each level of difficulty in the Detection Task of animal nouns. | |||

| Variables | Alcohol dependence with ADHD | Alcohol dependence without ADHD | Control Group |

| Level of difficulty | M (SE) | M (SE) | M (SE) |

| L2 | 4.60 (2.80) | 5.19 (1.72) | 6.70 (0.99) |

| L3 | 5.87 (2.85) | 6.06 (2.29) | 8.30 (0.99) |

| L4 | 8.80 (3.65) | 8.88 (2.12) | 12.00 (1.20) |

| L5 | 10.93 (4.52) | 11.06 (2.62) | 14.33 (2.15) |

| M=Mean; SE=Standard Error. | |||

Furthermore, a patient of the experimental group has not completed the task of working memory in full, so the sample examined for this test is equal to 61. With regard to the results obtained from the Detection Task of animal nouns, Table 3 showed means and standard deviations of accuracy (number of correct answers) of the three groups of participants examined in the detection task of target for each level of difficulty (numbers of words to be remembered for each list, from 2 to 5 words). The Test of Between-Participants Effects has shown a significant difference (p<.05) amongst the three groups of participants (F(6.174)=2.38, p<0.05, η²=0.076).

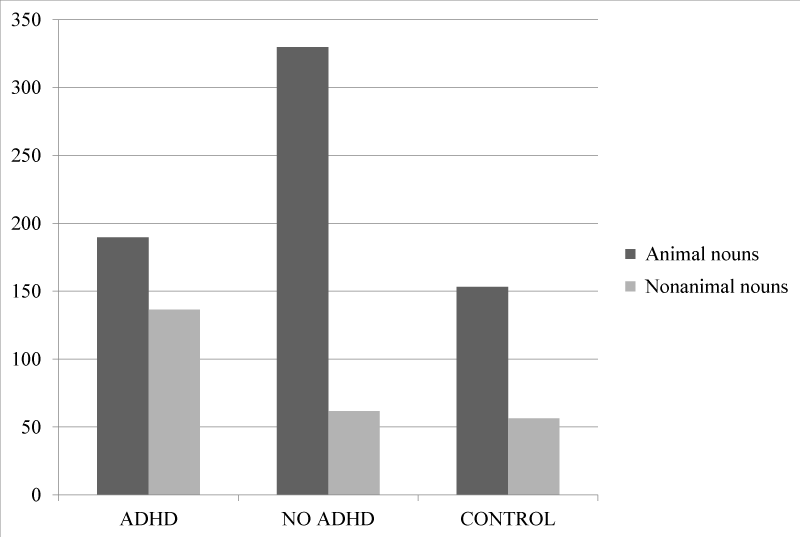

Particularly, control group differs from the other groups examined because it has issued a greater number of correct answers, committing fewer errors (nor intrusion nor inventions) compared to the experimental group of participants with and without the syndrome, in all levels of difficulty. The comparison of the averages with the Post Hoc, by using the critical value 1.34, showed an Effect of interaction between variables and Difficulty Level Group of subjects examined. This reveals that the passage from one level of difficulty to the next affects the number of correct responses from the sample, however, this occurs in a manner proportional to all three groups. In analyzing the working memory task, starting from the level of difficulty 3, emerged a significant Familiarity Effect (F (1.58) = 47.32 p<0.05 η²=0.449), called the Priming Effect.

The factor familiarity represents the critical comparison between items processed whilst performing the working memory task (old items) and items never listened to during the task (new items). Figure 2 examined the cost of inhibition of irrelevant items to the Lexical Decision inhibition-priming Task, given by the difference in response times recorded for the task of recognition of old items (i.e., previously presented in the task of primary recall) and new items (that never appeared in the test) for the category “animal nouns” and the category “nonanimal nouns”. You got the effect of activation/inhibition also called Priming Effect.

Figure 2: Priming Effect: cost in response time of irrelevant items as a function of previous activation in Lexical Decision Task at the Level of difficulty 3.

Therefore, control group significantly differed from the other two group of participants examined; the group with ADHD instead only significantly differed from the control group with regard to the “nonanimal nouns” category, and the group without ADHD only significantly differed from the control group for “animal nouns” category. For these two groups of participants may show a negative priming effect indicative of a higher cost of inhibition of items belonging to the “nonanimal” category for participants with ADHD and the category “animal” for participants without ADHD. This fact suggested that the response to the stimulus appeared delayed or affected by the activation attributed to the stimulus in the previous task, not relevant to the task but still activated and not fully controlled probably just due to a deficit of the executive functions and inhibitory control. This lack of control may have affected the efficiency in the working memory task [20-22].

Discussion

The aim of this study was to retrospectively investigate the comorbidity of ADHD primary symptoms and alcohol addiction in a sample of adult alcohol-dependent. From the administration of the Brown Scales, it emerged that the percentage of participants affected by dependence of alcohol comorbidity with a disorder of Hyperactivity and Inattention deficit ADHD was meaningful (50% of the total alcohol-dependent patients). Among these participants, 28.12% showed criteria for ADHD highly probable, 12.50% for ADHD probable but not certain and 9.38% for ADHD possible but not likely. Furthermore, a diagnostic division of ADHD subtypes was carried out according to the criteria of DSM-IV. From the alcohol-dependent group, 37.5% fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for the “hyperactivity-impulsive type”, 18.7% the “inattentive type” and 6.2% the “combined type”. These findings confirmed previous studies which showed high comorbidity of ADHD with addictive illnesses [13,23,24]. For example, Ohlmeier and colleagues [13,25] explored the different ADHD subtypes in adults with alcohol and substance addiction and found significantly higher values among these patients for the “inattentive type” and the “combined type”.

Furthermore, our study proposed to investigate deficits in executive functions (i.e., visual selective attention, shifting ability and interference control) among participants with ADHD and Alcohol Dependence. Results showed several deficits in the visual selective attention and in the interference control among alcohol patients with ADHD compared to the control group. In particular, alcohol-dependent patients with ADHD performed worse on the Trail Making Test, which is a task that requires advanced planning and metal flexibility, compared to both alcohol-dependent patients without ADHD and the control group. These findings confirmed previous studies conducted with adults with ADHD [17,26].

The examination of inhibitory control showed a poor performance for ADHD adults who had failed the activation control of irrelevant information in a lexical decision task. Specifically, the items that should be suppressed, and consequently interfering, were still largely accessible in the adult participants with alcohol dependence both with and without ADHD. A possible explanation of these results seems to be an inefficient mechanism underlying the inhibitory control which influences cognitive functions. These results concur with the hypothesis according to which the working memory task requires the control of irrelevant information both the more and the less activated, animal and non-animal nouns respectively.

These findings have important clinical implications since offer direct information about the activation control problem affecting working memory and the evidence is not limited, as in previous studies, to indirect measurements [27,28]. These group differences may also be explained by an inefficient use of strategies of verbal stimuli. The inadequate use of efficient strategies has been previously found in patients with frontal lobe lesions [26,29]. Further research on the underlying verbal learning strategies and on the general learning processes in adult participants with ADHD are necessary to confirm these findings.

When interpreting our results, it is necessary to highlight some limitations. First of all, the sample size was small but this was an exploratory study and the results cannot be considered as representative of the general population. Further studies with larger samples are required in order to confirm the comorbidity of alcohol dependence with ADHD. Secondly, we examined ADHD and executive functions deficits among adult populations using a cross-sectional design, as previous studies did [13,25]. Future studies should investigate patients since their childhood using a life span point of view: a longitudinal approach could clarify the nature and direction of the relationships, the stability of the impairments in alcohol adults. A third limitation is that we examined only some executive functions because of our sample size: we recommend that future studies explore a larger test battery which includes a wider range of both executive and non-executive functions in order to obtain a complete cognitive assessment [30,31]. Lastly, it is necessary to point out that, due to the high levels of comorbid disorder in participants with ADHD, it is well known that many of these associated conditions act directly modifying the person’s cognitive capacity [14,32,33]. It is therefore difficult to determine whether these cognitive deficits are attributed to the ADHD or to the presence of a comorbidity disorder, or to both.

Conclusion

This study revealed that adult alcohol-dependent patients had retrospectively high comorbidity with ADHD and significant current deficits of the executive functions.

The advantage of this study was to collect evidence of both current and past ADHD symptoms onset, and combining it with present cognitive performance of patients with alcohol dependence. Results would originally contribute to shed some light on the nature of the observed comorbidity between alcohol dependence and ADHD extending the analysis to potential cognitive deficit crucial for several psychiatric disorders.

These findings suggest the great importance of timely and adequate diagnostics and therapy of ADHD in order to prevent the onset of addictive illnesses.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed (DSM-IV). Washington, DC. 1994.

- Adler L, Cohen J. Diagnosis and evaluation of adults with ADHD. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2004; 27: 187-201. Ref.: https://goo.gl/g5xzde

- Biederman J, Faraone Stephen V, Wilens TE. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults. Am Med Association. 2004; 292: 619-623. Ref.: https://goo.gl/VjLSTK

- Cuffe SP, Visser SN, Holbrook JR, Danielson ML, Geryk LL, et al. ADHD and psychiatric comorbidity: functional outcomes in a school-based sample of children. J Atten Disord. 2015; 25: 1087054715613437. Ref.: https://goo.gl/4PZX6X

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, Biederman J, Conners CK, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006; 163: 716-723. Ref.: https://goo.gl/HkxvTf

- Biederman J, Wilens TE, Mick E, Milberger S, Spencer TJ, et al. Psychoactive substance use disorders in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): effects of ADHD and psychiatric comorbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 1995; 152: 1652-1658. Ref.: https://goo.gl/RHNiaE

- Biederman J, Faraone SV. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2005; 366: 237-248. Ref.: https://goo.gl/HcagmL

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE, Merikangas KR. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005; 62: 617-627. Ref.: https://goo.gl/7rciFs

- Daurio AM, Aston SA, Schwandt ML, Bukhari MO, Bouhlal S, et al. Impulsive personality traits mediate the relationship between adult attention deficit hyperactivity symptoms and alcohol dependence severity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017; 42: 173-183. Ref.: https://goo.gl/hhYV4B

- Lee SS, Humphreys KL, Flory K, Liu R, Glass K. Prospective association of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and substance use and abuse/dependence: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011; 31: 328-341. Ref.: https://goo.gl/CNdsmz

- Kim D, Lee D, Lee J, Namkoong K, Jung YC. Association between childhood and adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in Korean young adults with Internet addiction. J Behav Addict. 2017; 6: 345-353. Ref.: https://goo.gl/cm1dFz

- Wilens TE. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and the substance use disorders: the nature of the relationship, subtypes at risk, and treatment issues. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2004; 27: 283-301. Ref.: https://goo.gl/HTdKoh

- Ohlmeier MD, Peters K, Te Wildt BT, Zedler M, Ziegenbein M, et al. Comorbidity of Alcohol and Substance Dependence with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Alcohol Alcohol. 2008; 43: 300-304. Ref.: https://goo.gl/p8W4k3

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, Spencer TJ, Mick E, Monuteaux MC, et al. Functional Impairments in adults with self-reports of diagnosed ADHD: a controlled study of 1001 adults in the community. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006; 67: 524-540. Ref.: https://goo.gl/m6bMro

- Seidman LJ, Valera EM, Makris N. Structural brain imaging of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005; 57: 1263-1272. Ref.: https://goo.gl/h5wUxc

- Seidman LJ, Valera E, Bush G. Brain function and structure in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2004; 27: 323-347. Ref.: https://goo.gl/M2Dm7i

- Alderson RM, Kasper LJ, Hudec KL, Patros CH. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and working memory in adults: a meta-analytic review. Neuropsychology. 2013; 27: 287-302. Ref.: https://goo.gl/8oajDg

- Lynskey MT, Hall W. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and substance use disorders: is there a causal link? Addiction. 2001; 96: 815-822. Ref.: https://goo.gl/Nju5RP

- Del Corno F, Lang M, Schadee H. Brown ADD Scales Taratura Italiana, Firenze: Giunti OS. 2010.

- Palladino P. The role of interference control in working memory: a study with children at risk of ADHD. Q J Exp Psychol. 2006; 59: 2047-2055. Ref.: https://goo.gl/pvFqwZ

- Palladino P, Ferrari M. Interference control in working memory: Comparing groups of children with atypical development. Child Neuropsychol. 2013; 19: 37-54. Ref.: https://goo.gl/U9rsSt

- Hurks PP, Jolles J, Krabbendam L, Marchetta ND. Interference control, working memory, concept shifting, and verbal fluency in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Neuropsychology. 2008; 22: 74-84. Ref.: https://goo.gl/UgRZxX

- Willcutt EG, Doyle AE, Nigg JT, Faraone SV, Pennington BF. Validity of the executive function theory of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A meta-analytic review. Biol Psychiatry. 2005; 57: 1336-1346. Ref.: https://goo.gl/UYTn7B

- Wilens TE, Martelon M, Joshi G, Bateman C, Fried R, et al. Does ADHD predict Substance-Use Disorders? A 10-year follow up study of young adults with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011; 50: 543-553. Ref.: https://goo.gl/hcrn2y

- Ohlmeier MD, Peters K, Kordon A, Seifert J, Wildt BT, et al. Nicotine and alcohol dependence in patients with comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Alcohol Alcohol. 2007; 42: 539-543. Ref.: https://goo.gl/zdN4nJ

- Woods SP, Lovejoy DW, Ball JD. Neuropsychological characteristics of adults with ADHD: A comprehensive review of initial studies. Clin Neuropsychol. 2002; 16: 12-34. Ref.: https://goo.gl/2UFXbQ

- Carretti B, Cornoldi C, De Beni R, Palladino P. What happens to information to be suppressed in working memory tasks? Short and long term effects. Q J Exp Psychol. 2004; 57: 1059-1084. Ref.: https://goo.gl/1nYfPk

- Re A, De Franchis V, Cornoldi C. Working memory control deficit in kindergarten ADHD children. Child Neuropsychol. 2010; 16: 134-144. Ref.: https://goo.gl/G4wLRQ

- Van Der Elst W, Van Boxtel MP, Van Breukelen GJ, Jolles J. The Concept Shifting Test: Adult normative data. Psychol Assess. 2006; 18: 424-432. Ref.: https://goo.gl/eriy5n

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Newcorn JH, Kollins SH, Wigal TL, et al. Motivation deficit in ADHD is associated with dysfunction of the dopamine reward pathway. Mol Psychiatry. 2011; 16: 1147-1154. Ref.: https://goo.gl/jxRwys

- Carpentier PJ, De Jong AJ, Dijkstra AG, Verbrugge AG, Krabbe FM. A controlled trial of methylphenidate in adults with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and substance use disorders. Addiction. 2005; 100: 1868-1874. Ref.: https://goo.gl/9f79pH

- Biederman J. Impact of Comorbidity in Adults with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004; 65: 3-7. Ref.: https://goo.gl/sYTqhe

- Knutson CK, O’Malley M. Adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A survey of diagnosis and treatment practices. J Am Acad Nurse Pratictioners. 2010; 22: 593-601. Ref.: https://goo.gl/eJ42Vd