Case Report

Lateralized Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy presenting with recurrent Lacunar Ischemic Stroke

Yi Li*, Ayman Al-Salaimeh, Elizabeth DeGrush and Majaz Moonis*

Department of Neurology, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, 01655, USA

*Address for Correspondence: Yi Li, Department of Neurology, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA, 01655, Email: [email protected]

Dates: Submitted: 29 July 2017; Approved: 29 August 2017; Published: 30 August 2017

How to cite this article: Li Y, Al-Salaimeh A, DeGrush E, Moonis M. Lateralized Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy presenting with recurrent Lacunar Ischemic Stroke. J Neurosci Neurol Disord. 2017; 1: 029-032. DOI: 10.29328/journal.jnnd.1001005

Copyright License: © 2017 Li Y, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Cerebral amyloid angiopathy; Lateralization; Ischemic stroke

Abstract

Here we reported an interesting case of an 84-year-old woman with acute onset of paresis of left arm and paresthesia of left face and arm. The symptoms resolved within two hours. She also had a similar prior episode two weeks ago with only left arm paresthesia. Her MRI revealed different stages of lacunar ischemic lesions. Interestingly, the SWAN sequences showed lateralized rather than global multiple microhemorrhages over the right MCA and PCA territory, and the sulcal hyperintensity on FLAIR was also seen with no associated susceptibility effect and minimal enhancement, indicating probable cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) based on Boston Criteria.

It has been acknowledged that the CAA could manifest with certain localization preference. Cerebral microinfarct and white matter disease in CAA have been more often observed in the posterior circulation territory, however the restricted lateralization reported in our case has not been seen. Since CAA is often diagnosed when the characteristic MRI findings are picked up incidentally, recognizing this as a potential “TIA mimic” will be important for guiding treatment due to its higher risk of bleeding. In summary, this case highlights that the CAA could present as restricted lateralized lesions and occur as transient neurologic deficits, which to our knowledge has not be reported before. Recognition of it as a potential manifestation of CAA will be valuable in the clinical diagnosis process.

Case Report

An 84-year-old woman with history of diabetes, hypothyroidism, and hyperlipidemia presented with acute onset of paresis of left arm and paresthesia of left face and arm. She had a similar prior episode two weeks ago with only left arm paresthesia. She had a similar prior episode two weeks ago with only left arm paresthesia. On the initial encounter, the patient exam revealed BP of 150/46 and normal sinus rhythm. Neurological exam showed reduced pinprick and light touch sensations over the left side of the face, arm and leg, and mild weakness on the scale of 4/5 of the left upper extremity. The above symptoms resolved within two hours. Her workup including glucose level, vasculitis panel, ECHO and EKG, which were all normal. Carotid duplex revealed mild stenosis of the ICA bilaterally. CT angiogram of head and neck showed no hemodynamically significant stenosis, aneurysm, dissection or vascular malformation of the head and neck. No focal or multifocal segmental narrowing of vessels were seen. EEG did now show any abnormalities. Telemetry did not reveal an evidence of atrial fibrillation. Lumbar puncture was not performed.

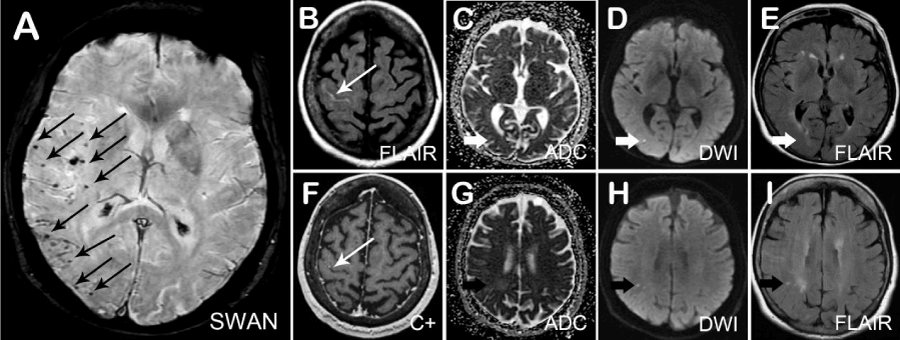

The MRI revealed different stages of lacunar ischemic lesions. Interestingly, the SWAN sequences showed lateralized rather than global multiple microhemorrhages over the right MCA and PCA territory, and the sulcal hyperintensity on FLAIR was also seen with no associated susceptibility effect and minimal enhancement (Figure 1), indicating probable cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) based on Boston Criteria [1].

Figure 1: Magnetic Resonance Imaging of lateralized cerebral amyloid angiopathy presented as recurrent ischemic stroke.

She received one year follow up and showed good prognosis, which she did not have any further similar episodes.

Discussion

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is characterized by the deposition of fibrillar protein with beta-pleated sheet configuration in the media and adventitia of small cortical and leptomeningeal arteries and capillaries [2]. Previous studies based on autopsy observation revealed that the risk of CAA increased with age, which was around 38% between 80-89 years reached up to 42% in patient above the age of 90 [3]. CAA encompasses specific cerebrovascular traits including spontaneous lobar intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), cognitive impairment, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and transient focal neurological episodes, with characteristic imaging manifestation of lobar ICH, cortical superficial siderosis, white matter changes, microhemorrhage and microinfarct.

Interestingly in our case report, the microbleeds were strictly lateralized and predominantly in the MCA supplied territory, rather than in a diffused pattern. It has been acknowledged that the CAA could have certain localization preference. One previous case report described a unilateral predominance of lobar hemorrhages which proven to be CAA by autopsy [4]. Cerebral microhemorrhage, one of the key radiological findings for the diagnosis of CAA [1], has a significant predilection in the cortical area, and appears to be more dominant in parietal lobe, rather than temporo-occipital lobes when compared to hypertensive microbleed [5]. The most involved vascular territory in CAA has been reported to be middle cerebral artery territory [5], as also seen in our case, which is not surprising since it is one of the major vessels that supply cortical areas. Additionally, microinfarct, another probably underestimated MRI finding [6], were more frequently seen in the occipital cortex in the scenario of CAA [7], and similarly the high correlation between posterior distribution of white matter disease and CAA have been seen [8]. It remains unclear what causes the unusual features of the multiple microhemorrhages confined to one hemisphere, as discovered in our case. One hypothesis is that the observed lateralized localization pattern might be in a different developmental stage of CAA. Another hypothesis could be that certain precipitating factors of this patient’s situation were unique, such as genetic background, promoting the deposit of amyloid in a lateralized pattern. Further studies to explore the epidemiology including the predominance of this phenomenon, the associated neurologic semiology and potential genetic association will be very interesting to investigate.

Other differential diagnosis for this case include amyloid-β–related angiitis (ABRA) or CAA-related inflammation (CAA-RI). CAA-RI involves perivascular inflammation but without angiodestruction, and ABRA involves granulomatous inflammatory processes and angiodestruction [9,10]. CAA-RI and ABRA patients are associated with extensive white matter abnormalities as well as leptomeningeal enhancement [9-11], while multiple lobar microbleeds present on gradient-echo sequences with or without subarachnoid hemorrhage, are hallmarks of CAA [12]. Without pathology evidence, it is difficult sometimes to make a definite diagnosis whether it is CAA or with concomitant inflammation component as CAA-RI or ABRA. Since our patient has good prognosis without immunosuppressive treatment, minimal white matter and leptomeningeal enhancement, and not presenting with any classic symptoms of headache, mental status changes, hallucination which was often seen in ABRA, the diagnosis clinically is leaning towards CAA.

Although clinically diagnosed CAA is usually seen in elderly patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage and cognitive impairment; it has also been recognized that CAA could also present as a potential cause of recurrent neurologic deficits [13], which appears to be either positive or negative phenomenon, and could be due to the irritation of cortical siderosis with and cortical microbleed, or manifestation of small vessel diseases. Clinically diagnosed CAA without ICH first evaluated for the recurrent neurologic deficits bear a higher burden of cortical superficial siderosis, white matter changes, and a trend with increased microbleed [14]. Since CAA is often diagnosed when the characteristic MRI findings are picked up incidentally, recognizing this as a potential “TIA mimic” will be important for guiding treatment due to its higher risk of bleeding.

Conclusion

In summary, this case highlights that the CAA could present as constricted lateralized lesions and occur as transient neurologic deficits, which to our knowledge has not be reported before. CAA should be considered as a differential etiology when encountering TIA or stroke, and recognition of the possible lateralized lesion pattern in CAA would also assist with clinical diagnose process.

Reference

- Knudsen KA, Rosand J, Karluk D, Greenberg SM. Clinical diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: validation of the Boston criteria. Neurology. 2001; 56: 537-539. Ref.: https://goo.gl/WjSJnQ

- Viswanathan A, Greenberg SM. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in the elderly. Ann Neurol. 2011; 70: 871-880. Ref.: https://goo.gl/du5nK2

- Masuda J, Tanaka K, Ueda K, Omae T. Autopsy study of incidence and distribution of cerebral amyloid angiopathy in Hisayama, Japan. Stroke. 1988; 19: 205-210. Ref.: https://goo.gl/i92uDE

- Morton-Bours EC, Skalabrin EJ, Albers GW. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy with unilateral hemorrhages, mass effect, and meningeal enhancement. Neurology. 1999; 53: 233-234. Ref.: https://goo.gl/jchJeP

- Lee SH, Kim SM, Kim N, Yoon BW, Roh JK. Cortico-subcortical distribution of microbleeds is different between hypertension and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. J Neurol Sci. 2007; 258: 111-114. Ref.: https://goo.gl/oZaA8o

- Van Veluw SJ, Charidimou A, Van der Kouwe AJ, Lauer A, Reijmer YD, et al. Microbleed and microinfarct detection in amyloid angiopathy: a high-resolution MRI-histopathology study. Brain. 2016; 139: 3151-3162. Ref.: https://goo.gl/hz1YPf

- Kovari E, Herrmann FR, Gold G, Hof PR, Charidimou A. Association of cortical microinfarcts and cerebral small vessel pathology in the ageing brain. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2016. Ref.: https://goo.gl/Gd4LNi

- Thanprasertsuk S, Martinez-Ramirez S, Pontes-Neto OM, Ni J, Ayres A, et al. Posterior white matter disease distribution as a predictor of amyloid angiopathy. Neurology. 2014; 83: 794-800. Ref.: https://goo.gl/X8jzJ9

- Scolding NJ, Joseph F, Kirby PA, Mazanti I, Gray F, et al. Abeta-related angiitis: primary angiitis of the central nervous system associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain. 2005; 128: 500-515. Ref.: https://goo.gl/h69HHe

- Malhotra K, Magaki SD, Cobos Sillero MI, Vinters HV, Jahan R, et al. Atypical case of perimesencephalic subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neuropathology. 2017; 37: 272-274. Ref.: https://goo.gl/GJ5hwT

- Salvarani C1, Hunder GG, Morris JM, Brown RD Jr, Christianson T, et al. Aβ-related angiitis: comparison with CAA without inflammation and primary CNS vasculitis. Neurology. 2013; 81: 1596-603. Ref.: https://goo.gl/Cd51Ws

- Moussaddy A, Levy A, Strbian D, Sundararajan S, Berthelet F, et al. Inflammatory Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy, Amyloid-β-Related Angiitis, and Primary Angiitis of the Central Nervous System: Similarities and Differences. Stroke. 2015; 46: e210-213. Ref.: https://goo.gl/QHtBfD

- Charidimou A, Peeters A, Fox Z, Gregoire SM, Vandermeeren Y, et al. Spectrum of transient focal neurological episodes in cerebral amyloid angiopathy: multicentre magnetic resonance imaging cohort study and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2012; 43: 2324-2330. Ref.: https://goo.gl/4zknF4

- Boulouis G, Charidimou A, Jessel MJ, Xiong L, Roongpiboonsopit D, et al. Small vessel disease burden in cerebral amyloid angiopathy without symptomatic hemorrhage. Neurology. 2017; 88: 878-884. Ref.: https://goo.gl/bXgN8Y